Leading steelmakers are having to review their previously approved decarbonisation strategies and make significant demands on governments.

Hydrogen prices remain high

According to European steel market consultancy GMK Center, there are currently three main methods for reducing CO₂ emissions in steelmaking.

The first is to use renewable energy to smelt steel using electric arc furnaces (EAFs) using scrap steel as feedstock (R-EAFs). The second is to produce direct reduced iron (DRI) using hydrogen to reduce iron by up to 99.99%, then smelt it in an EAF. Finally, electrolysis of molten iron oxide (MOE).

The third option is the most technologically complex. The first option also has its limitations because EAFs use scrap as an input material – a source of supply that is becoming increasingly unstable.

Setting up a direct hydrogen reduction system from iron ore could completely eliminate the blast furnace – the main component of the BF-BOF process, which is the largest source of CO₂ emissions in the steel industry.

As a result, leading European steelmakers have chosen option 2 as their main direction. For example, in July 2021, ArcelorMittal SA announced the construction of an H2 DRI plant in Gijón, Spain, with a capacity of 2.3 million tons/year and a total investment of about 1 billion euros.

The plant was expected to be operational in 2025 and supply feedstock to ArcelorMittal's EAF facility in Sestao. However, by the end of November last year, the group officially announced the indefinite postponement of the project due to unfavorable market conditions, high energy prices and slow development of green hydrogen infrastructure.

Germany’s largest steelmaker, Thyssenkrupp AG, is also facing similar problems. At the end of March, it indefinitely postponed a tender for green hydrogen for its H2 DRI plant in Duisburg (2.5 million tons/year). The tender was only announced in February 2024.

“The situation shows that the proposed price is much higher than expected, and the conditions for the hydrogen industry, which is developing more slowly than expected, are also subject to major changes,” the group said.

At the end of March, S&P Global estimated the cost of producing green hydrogen using alkaline electrolysis in Germany at 9.35 euros/kg. In December last year, this figure was even higher at 14.5 euros/kg – a very high level.

However, the Duisburg plant needs 151,000 tons of hydrogen over 10 years, a “huge” number. As a result, hydrogen steelmaking projects in Europe are currently stalled.

In this context, R-EAF technology using scrap is becoming a top priority for decarbonizing the steel industry. But it is not easy.

Consumer response

It is not entirely true that the high cost of green steel is the main barrier. If buyers are truly willing to pay a premium, then cost is not an issue – but the reality shows otherwise.

Carmakers such as General Motors, Jaguar Land Rover, Volvo, Mercedes-Benz and Volkswagen have pledged to use 100% zero-emission steel by 2050. But 2050 is still a long way off.

In 2024, ArcelorMittal Europe sold 400,000 tonnes of XCarb zero-emission steel – double the previous year. However, this figure is still too small compared to total consumption, and in February this year, the group announced a partial suspension of its decarbonization plans in Europe.

“Although customers are interested in low-emission steel, they are not willing to pay more. Therefore, they cannot buy it, because we only sell it at a higher price,” explains Genuino Cristino, ArcelorMittal’s CFO.

According to Fastmarkets, in mid-April, the premium for green steel in the EU was €200–300/tonne depending on CO₂ emissions. Meanwhile, buyers were only willing to pay €100–150. Mill representatives said that the maximum discount they could accept was only €20–30/tonne. Supply and demand are therefore very far apart.

“In our assessment, the premium for green steel is likely to be short-lived and not a decisive factor for investing in the green transition,” said Stanislav Zinchenko, CEO of GMK Center.

Key conditions

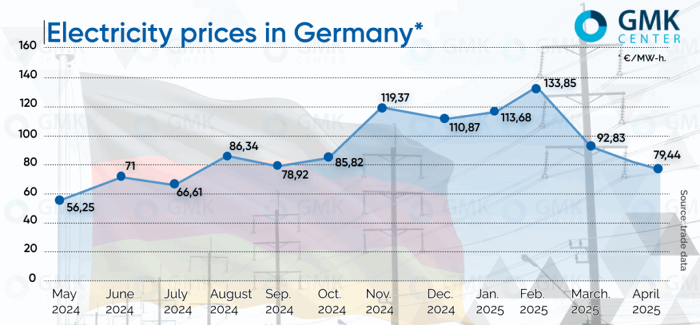

The CEO of ArcelorMittal Germany, Thomas Bünger, believes that the main reason for the delay in the decarbonization plan is the high cost of electricity. According to him, the acceptable price for steel production using EAFs is around 50–55 euros/MWh – the same as before the energy crisis. However, electricity prices in Germany have long exceeded this level.

Electricity prices in Germany over the past year (Unit: euro/MWh, source GMK Center)

Cheap electricity has therefore become a key element of the European steel industry’s decarbonisation strategy. In late April, ArcelorMittal Poland’s CEO Wojciech Koszuta said that the group was ready to convert its Dąbrowa Górnicza plant from BF-BOF to R-EAF on a large scale, if competitive electricity prices were guaranteed.

Obviously, the market cannot guarantee this – only governments can. In this case, the Polish government. They need to come up with appropriate policies. However, Warsaw, like other European capitals, is not in a hurry to meet the steel industry’s demands.

Against this backdrop, the Czech Republic’s largest steelmaker, Trinecke zelezarne, postponed major decarbonisation projects at the end of April, for at least two years. This includes plans to build an electric arc furnace and related infrastructure at the Tršinka plant.

Just a month earlier, the Czech government had signed a memorandum of understanding pledging to support the company. But it seems that all that has been done is on paper. As a result, the green transition is stalling – not just for Trinecke, but for the entire European steel industry.

Clearly, this can only happen if three conditions are met simultaneously: cheap electricity, economically viable hydrogen technology, and public investment. Because companies cannot shoulder all the costs themselves.

ArcelorMittal estimates that it would cost up to $40 billion to decarbonize its entire European operations – a huge sum, even for the world’s second-largest steelmaker. State funding is therefore essential, but the current level of support is still very limited.

As of February 2025, the group had received a total of more than 3.5 billion euros from governments. In total, current state support has not yet reached 10% of the total project cost.

Vietnambiz

English

English  Vietnamese

Vietnamese

.jpg)

w300.jpg)